Agents

Agent definitions

- Agent: something that takes in information from its surroundings (sensors) and does something in response (actuators)

- Agent function: rule or process that tells an agent what actions to take

- Agent program: the actual implementation of the agent function

- Percept: agent sensor input (text, images, sounds, etc.)

- Percept sequence: chatgpt history (history of what the agent has had as inputs)

- Rational: reasonably correct (does not need to be perfect), depends on 4 things:

- performance measure

- agent’s prior knowledge of the environment

- actions the agent can perform

- percept history to date

- Rational agent: an agent that selects the action that maximizes performance measure (“does the right thing”)

- Performance measure: a way to judge how well an agent is doing its job (e.g. chess game → win rate, self driving car → reaching destination safely and quickly, recommendation system → how often users click/like suggestions)

- PEAS framework:

- Performance measure

- Environment: the surroundings the agent operates in

- Actuators: the parts that lets the agent take action (wheels, arms, display, …)

- Sensors: the parts that let the agent perceive or gather information (camera, microphone, GPS, …)

Environment types:

- Fully observable vs partially observable

- Fully observable: agent can see everything it needs to make a decision (e.g. chess)

- Partially observable: agent only sees part of the environment (e.g. driving in fog)

- Deterministic vs stochastic

- Deterministic: the next state is completely determined by the current state and action (no randomness)

- Stochastic: there is some randomness in what happens next

- Episodic vs sequential

- Episodic: each action is independent → what you do now doesn’t effect the next (e.g. image recognition)

- Sequential: actions build on each other, past decisions matter (e.g. chess, driving)

- Static vs dynamic

- Static: environment doesn’t change while the agent is thinking (e.g. crossword puzzle, sudoku)

- Dynamic: environment changes over time, even if the agent is not acting (e.g. real world, driving)

- Discrete vs continuous

- Discrete: limited number of possible states (e.g. chess, other board games)

- Continuous: states and actions can take any value (e.g. driving speed, robot arm angles)

- Single vs multi agent

- Single-agent: only one agent is acting (e.g. solving a maze)

- Multi-agent: multiple agents interact, possibly competing or cooperating (e.g. soccer, trading bots)

Agent types

-

Simple reflex agent: acts only based on current situation, uses conditional rules

- only works in fully observable environments

-

Model-based reflex agent: keeps some internal memory (model) of the world, uses current input and past information to decide what to do

- used in partially observable environments

-

Goal-based agent: has specific goals it tries to achieve, can plan ahead and compare different possible outcomes

-

Problem-solving agent: a type of goal-based agent that uses search and planning to find a way to reach its goal

- Problem-solving cycle:

- goal formulation → define desirable states

- problem formulation → identify states and actions relevant to goal

- search → find sequences of actions that reach goal

- execution → carry out actions — Utility-based agent: tries to maximize performance, uses utility function to measure how good each action is

- utility: numerical value representing how desirable an outcome is; utility-based agents choose actions with highest expected utility

- Problem-solving cycle:

-

Learning agent: improves over time by learning from experience

Genetic Algorithms

Darwinian Evolution Principles

- Survival of the fittest: resources are limited, only the most adaptable individuals reproduce, selection ensures only efficient competitors survive

- Diversity drives change:

- behavioural/physical differences are partly inherited, partly random

- traits increasing reproduction chances and heritable → spread over generations

- leads to new combinations and evolutions of species

- Population dynamics:

- population = unit of evolution

- individual = unit of selection

- random variations + selection = constant diversity source

- no guiding force → evolution is emergent, not directed

Natural & biological evolution

- Alleles: possible values of a gene

- Chromosomes: long DNA molecules containing many genes

- Genome: complete genetic material

- Genotype: gene set of an individual

- Phenotype: observable characteristics from genotype

- Key conditions for evolution:

- Reproduction with inheritance: individuals make copies of themselves

- copies should resemble their parents (not be duplicates)

- Variation: ensure that copies are not identical to parents

- mutations, crossover produces individuals with different traits

- Selection: need a method to ensure that some individuals make copies of themselves more than others

- fittest individuals (favourable traits) have more offspring than unfit individuals, and population therefore has those traits

- over time, changes will cause new species that can specialize for particular environments

- Reproduction with inheritance: individuals make copies of themselves

Genetic Algorithms

| Natural Concept | Genetic Algorithm Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Chromosome | solution representation |

| Gene | feature or variable |

| Allele | feature falue |

| Locus | gene position |

| Genotype | encoded structure (solution encoding) |

| Phenotype | decoded solution (actual parameters) |

Main steps

- Initialization: generate initial population

- Evaluation: compute fitness for each solution

- Selection: choose individuals for reproduction

- Crossover: mix parents to create children

- Mutation: introduce random variations

- Replacement: update population for next generation

- Termination: stop when condition met (e.g. max generations, target fitness hit)

Key variants

- Simple GA (SGA): full population replaced each generation

- Steady-state GA: only a few individuals replaced each iteration

- elitism: copy a few best individuals unchanged into the next generation so high-fitness solutions are preserved

Selection methods

- Tournament selection: select random individuals and keep the best for reproduction, repeat until you have a chosen amount of parents

- Roulette wheel selection: probabilistic selection based on fitness,

Premature Convergence

- the population consists of similar individuals, it reduces likelihood of finding new solutions

Genetic Operators

- Crossover: a method of combining two candidates from. the population to create new candidates

- Mutation: lets offspring evolve in new directions → introduces a certain amount of randomness (certain traits may become fixed)

- Replication: copy an individual

Crossover Operations

- 1-point crossover:

Step 1: Choose random crossover point

P1: 1 2 3 | 4 5 6 7

P2: 7 6 5 | 4 3 2 1

↑ crossover point

Step 2: Swap segments after crossover point

C1: 1 2 3 | 4 3 2 1

C2: 7 6 5 | 4 5 6 7

✅ Final Offspring

C1: 1 2 3 4 3 2 1

C2: 7 6 5 4 5 6 7

- 2-points crossover:

Step 1: Choose two random crossover points

P1: 1 2 | 3 4 5 | 6 7

P2: 7 6 | 5 4 3 | 2 1

↑ ↑

crossover points

Step 2: Swap middle segments between parents

C1: 1 2 | 5 4 3 | 6 7

C2: 7 6 | 3 4 5 | 2 1

✅ Final Offspring

C1: 1 2 5 4 3 6 7

C2: 7 6 3 4 5 2 1

- Uniform crossover (UX): each gene has a 50% chance of being inherited from either parent

Step 1: Generate random mask

P1: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Mask: 1 0 1 0 0 1 0

P2: 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Step 2: Copy by mask (1 → from P1, 0 → from P2)

C1: 1 6 3 4 3 6 1

C2: 7 2 5 4 5 2 7

✅ Final Offspring

C1: 1 6 3 4 3 6 1

C2: 7 2 5 4 5 2 7

- Order crossover (OX):

- copying a randomly selected set from the first parent

- filling the remaining positions with the order of elements from the second

Step 1: Copy randomly selected set from first parent

p1: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

p2: 9 3 7 8 2 6 5 1 4

c1: * * * 4 5 6 7 * *

c2: * * * 8 2 6 5 * *

Step 2: Copy rest from second parent in order

Remaining order from p2: 1, 9, 3, 8, 2

C1: 3 8 2 4 5 6 7 1 9

C2: ?

Step 1: Copy randomly selected set from first parent

p1: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

p2: 4 5 2 1 8 7 6 9 3

c1: * * * 4 5 6 7 * *

Step 2: Copy rest from second parent in order

Remaining order from p2: 9, 3, 2, 1, 8

C1: 2 1 8 4 5 6 7 9 3

- Uniform order crossover (UOX):

Step 1: Setup

Parents (P1, P2) and Mask

P1: 6 2 1 4 5 7 3

Mask: 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 → generate new mask for every 2 parents

P2: 4 3 7 2 1 6 5

Step 2: Copy Genes by Mask

- Copy genes from P1 → C1 where mask = 1

- Copy genes from P2 → C2 where mask = 1

C1: - 2 1 - 5 - 3

C2: - 3 7 - 1 - 5

Step 3: Fill Remaining from Opposite Parent

- Fill blanks (-) with remaining genes from the other parent in order

C1: 4 2 1 7 5 6 3

C2: 6 3 7 2 1 4 5

✅ Final Offspring

C1: 4 2 1 7 5 6 3

C2: 6 3 7 2 1 4 5

- Partially mapped crossover (PMX): preserves relative order and position (used for permutation problems)

Step 1: Select two crossover points

P1: 1 2 | 3 4 5 | 6 7 8

P2: 4 5 | 6 7 8 | 1 2 3

Step 2: Copy middle section from P1 → C1

C1: * * | 3 4 5 | * * *

Step 3: Map remaining genes from P2 using the mapping of swapped section

Mapping: 3↔6, 4↔7, 5↔8

Fill remaining using P2 order, applying mapping:

P2 order: 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3

→ Apply mapping to avoid duplicates

✅ Final Offspring

C1: 6 7 | 3 4 5 | 8 1 2

- Cycle crossover (CX): every gene comes from one parent in the same same index across cycles

Step 1: Find cycles based on position mapping

P1: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

P2: 3 7 5 1 6 2 4

Mapping:

1 → 3 (pos3) → 5 (pos5) → 6 (pos6) → 2 (pos2) → 7 (pos7) → 4 (pos4) → 1

Cycle: (1,3,5,6,2,7,4)

Step 2: Copy first cycle from P1, rest from P2

C1: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

C2: 3 7 5 1 6 2 4

✅ Final Offspring

C1: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

C2: 3 7 5 1 6 2 4

Mutation

- Inversion: reversed order of selected segment of genes

9 3 7 8 2 6 5 1 4 → 9 3 6 2 8 7 5 1 4

- Insertion: select one gene and insert it into a random position

9 3 7 8 2 6 5 1 4 → 9 7 8 2 3 6 5 1 4

- Displacement: select a subtour (continuous segment) and reinsert it somewhere else

9 3 7 8 2 6 5 1 4 → 9 8 2 6 5 3 7 1 4

- Reciprocal exchange (swap): select two genes and swap their positions

9 3 7 8 2 6 5 1 4 → 5 3 7 8 2 6 9 1 4

- Scramble mutation: select a subset of genes and randomly shuffle their order

9 3 7 8 2 6 5 1 4 → 9 3 6 8 7 2 5 1 4

EVERYTHING ABOVE IS PRE-MIDTERM

Games (Adversarial Search)

-

adversarial, multi-agent environments (MAX vs MIN)

-

defined by: initial state, legal moves, terminal test, utility

-

game tree → nodes = states, edges = moves, ply = depth layer

-

full search often impossible → rely on heuristics + cutoff

-

what makes a game different from normal search?:

- multi-agent, competitive, adversarial

- opponent affects your outcome

- need a strategy, not just a path

- goal: choose actions that maximize your payoff against an optimal opponent

Minimax

- idea:

- perfect play under deterministic, perfect-information games

- MAX chooses move with the highest worst-case value

- assume opponent is rational and tries to minimize your score

- procedure:

- expand game tree to some depth

- evaluate leaf nodes with evaluation function

- back up values:

- MAX nodes take max of children

- MIN nodes take min of children

- choose best move at root

- properties:

- complete (if tree finite)

- optimal (against optimal opponent)

- expensive: time, space

Alpha-beta pruning

- purpose:

- avoid evaluating branches that cannot affect the final decision

- works alongside minimax → same final answer, faster search

- key ideas:

- (alpha): best score MAX can guarantee so far

- (beta): best score MIN can guarantee so far

- if a branch is already worse than what a player can get elsewhere → prune it

- benefits:

- eliminates huge parts of tree

- with good move ordering, reduces time from to

- allows deeper search within the same time

Evaluation functions

- used when search is cut off early

- heuristic score estimating “how good” a state is

- usually weighted sum of features

- must correlate with probability of winning

Cutoff search

- search only to fixed depth (resource limits)

- evaluate non-terminal states using evaluation function

- risk: horizon effect (bad events hidden beyond depth)

Search enhancements

- iterative deepening: search 1 ply, then 2, then 3.. until time expires

- quiescence search: extend search in volatile positions (captures, threats)

- move ordering: improves alpha-beta effectiveness

- singular extension: explore unusually promising moves deeper

Swarm Intelligence

Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)

- population-based stochastic (some randomness) search using ants and pheromone

- ants choose edges probabilistically based on pheromone + visibility

- positive feedback: good paths get reinforced

- evaporation: keeps pheromone from exploding → forces exploration

- loop: create ants → build solution → evaporate → add pheromone

- needs graph representation; finite path

- issues: converges fast

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

- swarm of particles moving in search space

- each particle has position and velocity

- particles remember:

- personal best (pbest)

- global best (gbest)

- velocity updated using:

- momentum (old velocity)

- pull toward pbest

- pull toward gbest

- movement influenced by randomness → exploration

- fast convergence but may get stuck if swarm collapses early

Learning & Machine Learning

-

machine learning: programs that improve with experience

-

Mitchell’s definition: learns if performance on task T improves using experience E measured by P

-

checkers ML example (T/P/E):

- Task (T): play checkers

- Performance (P): % games won

- Experience (E): games of self-play used as training data

-

types of learning

- supervised: labeled data (classification, regression)

- unsupervised: no labels (clustering)

- reinforcement: reward-based learning

- exploration vs exploitation: balance between trying new actions to gather information vs using known high-reward actions

-

supervised examples: decision tree classifier, perceptron/NN classifier

-

unsupervised examples: k-means, hierarchical clustering

Designing a learning system

- choose training experience

- choose target function

- choose representation (rules, tables, linear model, neural networks)

- choose learning algorithm (e.g. gradient descent)

Memorization vs generalization

- memorization: model stores training examples, performs poorly on new data

- generalization: model learns underlying patterns, performs well on unseen data

- overfitting: too much memorization, not enough generalization

Training experience issues

- must be representative (training examples must reflect real situations the agent will face)

- e.g. if a spam filter is trained on only old emails, it won’t generalize to modern spam

- feedback may be direct (correct answer provided) or indirect (reinforcement → only rewards or signals)

- may or may not involve a teacher (provided correct labels vs learner must find structure)

- e.g. clustering animals without knowing categories

- bad data (noisy, biased, incomplete, incorrect labelling, …) harms performance

ML challenges

- model complexity:

- too simple → underfitting (can’t capture patterns)

- too complex → overfitting (memorizes training data)

- training data size: more data → generally better performance, too little → poor generalization

- noise in data: incorrect labels or irrelevant features degrade accuracy

- learnability limits: some things are inherently hard to learn

- e.g. predicting stock price → hard due to chaotic signals

- prior knowledge: using domain knowledge can constrain hypotheses and improve learning

- e.g. knowing legal moves in chess reduces search space → better performance

Decision Trees & Overfitting

Decision trees

- supervised learning method for classification

- recursively split data based on attributes

- internal nodes = tests; branches = outcomes; leaves = class labels

- good for data with clear, rule-line data

- handles discrete or continuous attributes (continuous → threshold tests)

How to build one

- choose attribute that best separates data

- common criteria:

- information gain (IG): reduction in entropy (uncertainty) after a split

- gain ratio: normalizes IG by attribute branching factor

- repeat splitting on subsets until:

- all examples in node have same class

- no attributes left

- data too small

Advantages

- interpretable (human-readable rules)

- fast to train

- little data preprocessing required

- can capture non-linear boundaries

Disadvantages

- unstable (small data changes → different tree)

- greedy splitting may miss globally optimal tree

- prone to oversplitting

- optimal tree size: finding the smallest decision tree is NP-hard → practical algorithms use greedy heuristics instead of exhaustive search

Overfitting (in decision trees)

- model becomes too specific to training data

- memorizes noise instead of learning patterns

- tree grows too deep with many small, impure leaves

Signs of overfitting

- high accuracy on training data & low accuracy on unseen data

- branches based on rare or noisy attribute combinations

Causes

- noisy data

- too many attributes

- insufficient training examples

- splitting until leaves are tiny (one or few samples)

Preventing overfitting

- pre-pruning: stop early

- limit tree depth

- minimum samples per node

- require split to exceed IG threshold

- post-pruning: build full tree, then trim

- remove branches that do not improve validation accuracy

- replaces overfitted subtrees with leaf nodes

- cross-validation: ensures splits generalize

- simplify attributes: remove irrelevant features

Neural Networks

- model made of neurons connected by weighted edges

- each neuron: sum of inputs → apply activation function → output

- learning = adjusting weights so outpus match targets

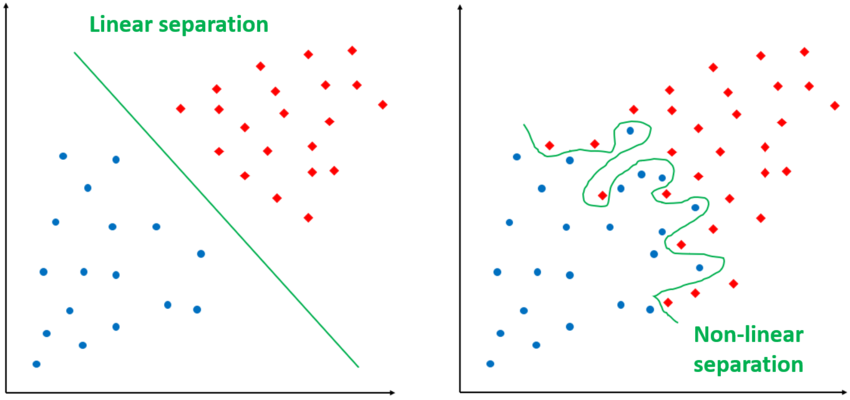

Perceptron (single layer network)

- linear classifier (straight line decision boundary)

- works only for linearly separable problems

- weight update rule reduces classification error

- limit: cannot learn XOR or any non-linear separation

Why multilayer networks?

- add hidden layers → can learn non-linear functions

- input → hidden (can be multiple) → output

- hidden units combine features → represent complex patterns

Activation functions

- a rule that transforms a neuron’s summed input into its output, adding the non-linearity needed for neural networks to learn complex patterns

- common forms:

- step/sign function: perceptron-style (not differentiable, not usable for backprop)

- sigmoid/tanh: smooth, differentiable → needed for backprop

- choice affects learning speed + representational power

Training neural networks

- forward pass:

- input flows through layers to produce prediction

- back-propagation (error-correcting learning):

- compare prediction to target → compute error

- send error backwards through network

- adjust weights using gradient descent

- requires differentiable activation functions

- intuition:

- if output is wrong → adjust weights that contributed to error

- small learning rate = stable but slow

- large learning rate = fast but unstable

Strengths

- learns complex, non-linear patterns (multi-layer)

- good for classification, pattern recognition, noisy data

- no need for explicit rules → model “discovers” structure

Limitations

- weights are a black box → poor interpretability

- can overfit (memorize training data)

- needs lots of data + careful tuning

- training may get stuck in local minima (gradient descent)

Clustering

- unsupervised learning: group similar data points without labels

- goal: high similarity within clusters, low similarity between different clusters

- works only if real structure exists in data

- results must be interpreted → algorithm will always produce clusters, even if meaningless

- examples: images, patterns, documents, shopping items, biological data, social networks

Hierarchical clustering

- builds a tree of nested clusters

- no need to pick the number of clusters beforehand

- two types:

- agglomerative: start with each point alone → repeatedly merge closest clusters

- divisive: start with all points together → repeatedly split

Linkage criteria (how to measure distance between clusters):

- single linkage: nearest points → long “chain-like” clusters

- complete linkage: farthest points → compact clusters

- average linkage: average distance → balances sensitivity

- centroid linkage: distance between cluster centroids

Limitations

- early merge/split decisions cannot be undone

- choosing where to “cut” the tree is subjective

Partitioning clustering

- choose (number of clusters) first

- assign points to clusters based on similarity to representatives

K-means

- most common partitioning clustering method

- tries to minimize distances between points and their cluster centers (centroids)

How it works

- pick initial centers

- assign each point to nearest center

- recompute centers

- repeat until stable

Strengths

- simple, fast, handles large datasets

- can adjust assignments if initial choices were bad

Weaknesses

- sensitive to initial needs

- not guaranteed to find the optimal clustering

- must choose manually

- can get stuck in local minima

Validation

- why validate?: clustering always produces groups → need to check if they’re meaningful

- ways to validate:

- internal: based on cluster quality (tightness, separation)

- external: compare to known labels or external variables

- relative: compare results across different values or algorithms

Common difficulties

- choosing the right number of clusters

- noise and outliers distort cluster structure

- results depend heavily on distance measure

- hard to visualize high-dimensional clusters

- multiple valid clusterings may exist for the same dataaf

Logic

Common Logic Symbols

| Symbol | Meaning | Example | Plain English Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| not | ”Not P” → P is false | ||

| and | P and Q are both true | ||

| or (inclusive) | At least one of A or B is true | ||

| implies | If P is true, then Q must also be true | ||

| biconditional (iff) | P is true exactly when Q is true | ||

| equality | x and y are the same object/value | ||

| universal quantifier (“for all”) | Everybody loves pizza | ||

| existential quantifier (“there exists”) | At least one student exists | ||

| relation between objects | Alice and Bob are friends | ||

| Function | returns an object | ”John’s father” | |

| Variables | placeholders for objects | P applies to some object x |

Knowledge Representation (KR)

- express knowledge in a form the agent can use

- good KR: explicit, concise, suppresses irrelevant detail, supports reasoning

Logic basics

- syntax: structure of a sentence

- semantics: truth in a model

- entailment: in all models of KB

- inference: derive new sentences; must be sound and complete

Propositional Logic (PL)

- simple true/false statements combined with , , , ,

- truth tables define semantics

- strength: simple, compositional

- weakness: cannot talk about objects/relations; low expressive power

Propositional Logic (PL) Examples

- Meaning: It is raining and it is cold.

- : “It is raining”

- : “It is cold”

- Meaning: If the door is not locked, then the alarm is on.

- : “The door is locked”

- : “The alarm is on”

- Meaning: Lights are on or motion is detected, and there is no power failure.

- : “Lights are on”

- : “Motion detected”

- : “Power failure”

First-Order Logic (FOL)

- adds objects, relations, functions, variables, quantifiers

- much more expressive than PL

First-Order Logic (FOL) Examples

- Meaning: Every student is smart.

- Meaning: John loves at least one person.

- Meaning: Richard is John’s brother, and John is a king.

FOL "at Google" patterns

- Meaning: Everyone at Google is smart.

- Meaning: Everyone is at Google, and everyone is smart.

- Meaning: Someone at Google is smart.

Quantifiers

- universal: → “for all x”

- correct pattern:

- existential: → “there exists x”

- correct pattern:

- quantifier properties:

- and commute with themselves, not with each other

- duality:

PL vs FOL

| Feature | PL | FOL |

|---|---|---|

| talks about | facts | objects + relations |

| variables | no | yes |

| quantifiers | no | , |

| expressiveness | low | high |

- implication equivalence: (X \rightarrow Y \equiv \neg X \lor Y) (tautology)

Philosophy & AI

Core questions

- what is a mind? how do human minds work?

- can non-human systems (like computers) have minds?

- what counts as thinking or understanding?

Weak & strong AI

- weak AI: AI produces useful tools and intelligent behaviour, but not real understanding or minds

- strong AI: a machine can literally have a mind, understanding, intentions, consciousness

- arguments raised against strong AI:

- some tasks may be impossible for computers, no matter how we program them

- certain designs of “intelligent programs” fail inherently

- programs may simulate intelligence without truly understanding

- practical limits: complexity, infeasibility of encoding full human cognition

Turing Test

- idea: if a machine can hold a conversation indistinguishable from a human, treat it as intelligent

- strengths:

- avoids metaphysical debates (“can machines think?”)

- focuses on observable behaviour

- critiques:

- measures performance, not inner understanding

- easy to foot naive interrogators

- does not assess reasoning, emotion, self-awareness

- machine may pass via tricks, not intelligence

- famous turing test objections:

- lovelace objection: machines cannot originate anything → they do what we tell them

- species-centricity: assumes humans must be more intelligent

- mathematical objection: godel style limits → formal systems cannot solve everything

- onsciousness objection: intelligence requires awareness, emotions, subjective experience

- diversity objection: humans vary widely; programs may not

Chinese room argument

- setup:

- person (doesn’t know chinese) goes in a room

- given chinese text (paragraphs) and questions, rules describing how to manipulate Chinese symbols from questions and text, and output corresponding Chinese text

- person is being the “computer processor”

- chinese room = syntax semantics; programs don’t understand

- claim:

- running a program (symbol manipulation) is not enough for understanding or intentionality

- strong AI is false: programs do not genuinely “understand” even if they behave correctly

- counterarguments:

- systems reply: the whole system understands, not the person

- brain simulator reply: simulating neural processes would produce understanding

- many mansions reply: non-digital mechanisms might produce real cognition

- robot reply (implied): embodiment may be required for meaning